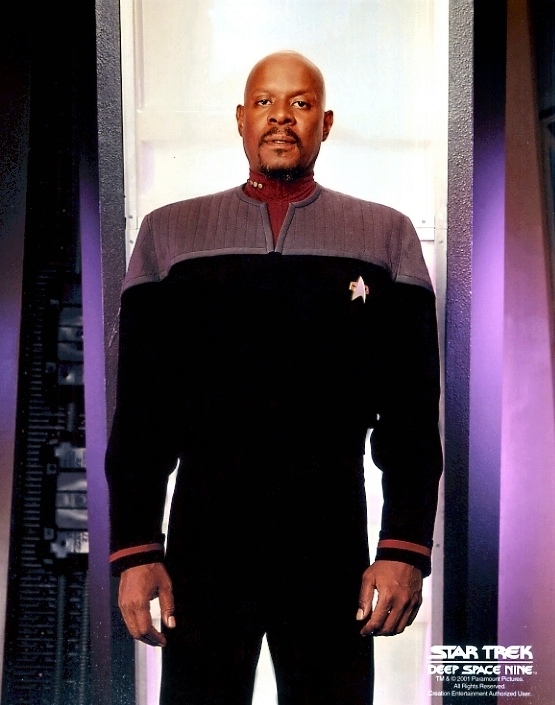

aerial view of Scientology’s “Hole”

One of the most troublesome aspects of the scientology cult, and cults in general, is that participation is apparently voluntary. People sign up of their own free will, and they remain a part of these groups by their own choice. In discussions about scientology’s ersatz executive prison on their Int Base, widely known as “the Hole”, the point is often made that a raid or rescue effort would be pointless. Most, if not all, of the church execs being confined there would tell any investigating authority that it is their choice to be there. There are accounts of some people being physically removed to the Hole by force, but there are also accounts of people who decided to leave and successfully pushed through the cult’s resistance to get out. It is hard to explain how that qualifies as forced confinement.

This being so, then what is the problem? This is a question often raised by those with little information on the subject, and by cult apologists as well. If people have consented to the way they are being treated, can we really call it abuse or a violation of their dignity? Is there anything to criticize in scientology, when we are talking about consenting adults who have chosen to be a part of that organization, or to exercise their parental rights to bring their children into it? In fact, what the hell are all you cult critics getting so wound up about? What could be so bad? Maybe you just don’t like scientology, or new religions, or maybe you are one of those suckers who got taken and now you are holding a grudge and that’s why you make these ridiculous claims about “dangerous cults”.

These are legitimate questions, I suppose. But they are rooted in certain incorrect assumptions about human psychology and behavior. More troubling, to me, they reflect a lack of compassion and concern for other people when they are suffering by their own hand, as it were. Laying aside the question of children and young adults who are abandoned to or coerced into the cult; we must respect the fact that consenting adults can be misled, preyed upon, and defrauded. As a society, we have laws against fraud and so on, that make it clear we do not wish to live in a “dog-eat-dog” environment where predators and con-men bear no responsibility so long as they get the consent of their victims. We have declared a collective intent to protect each other and ourselves from such wrongs; through the legal system, as well as on a human level through the sharing of information, observations, and warnings.

Dismissing cults as voluntary and their victims as weak-minded or gullible is part of a comforting mindset, which allows us to believe that we could never fall victim to such a thing, because we would never consent to be exploited or preyed upon. But this attitude fails to account for the reality of human nature. In reality, our thinking and decisions are not as self-directed as we wish to believe. There are many aspects of our own minds which are necessarily unconscious, and perhaps unexplored. There are many ways and opportunities to manipulate a person’s thinking, and to leave them believing beyond a doubt that their ideas and choices are their own. This information is widely available, from authors and others who often have developed methods to take advantage of this aspect of human nature. Anyone who wishes to thrive in advertising, or in prison, or as a con-artist, or as a guru, must master these methods of manipulation, and they do.

If we are ignorant of the reality of human vulnerabilty to mental manipulation, it only makes it easier for these folks to do what they do. When we say, “that could never happen to me, my mind is my own”, the manipulators are the first ones to agree. “Yeeeesss… that’s right. No reason to examine the matter further.” Ignorance and arrogance are a very dangerous combination, and a boon to manipulative predators. With these thoughts in mind, I want to share part of a paper I came across some time ago on the Ross Institute website. It addresses psychotherapy cults, and co-counseling in particular. The part I wish to share is a section titled “The Engineering of Consent”. It is an excellent exploration of the subject, and I hope you find it informative.

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

The following is an excerpt from:

“Group influence and the psychology of cultism within Re-evaluation Counselling: a critique”

By Dr. Dennis Tourish and Pauline Irving

The entire paper, including references, can be found here.

The engineering of consent

Consent or agreement with a certain theoretical orientation, freely given, implies that people retain the right to ask questions, examine alternative sources of information and review their initial commitment to the organisation concerned. What can be termed the engineering of consent threatens all these basic knowledge and action levels, undermining the right to withdraw consent and leave. Agreement is extracted through pressure, the right to question leaders is withheld, alternative sources of information are absent or ridiculed and people are systematically pressurised into escalating their level of involvement.

What has been termed ‘mind control’ operates by taking such aspects of social influence and exaggerating them to the extent that people’s thoughts, feelings and behaviour are manipulated to the greater gain of the manipulator, at the expense of the person being influenced (Zimbardo and Anderson, 1993). Clearly, most human interaction consists of attempts to influence the cognitions and behaviour of others, while interaction within a positive reference group is inherently inclined to encourage the development of shared norms and behaviours (Turner, 1991). However, cults are characterised by attempts to close down choice, restrict information flow, discourage the expression of dissent, focus group norms along narrowly prescribed lines, exaggerate participants’ sense of commitment by extracting public statements of loyalty (often after participation in faintly humiliating rituals) and dominate the normal thinking process of affected individuals (Hassan, 1988). Conway and Siegelman (1992) describe the communication techniques of American cult leaders as follows:

“Most rely on the use-and abuse- of information: on deceptive and distorted language, artfully designed suggestion and intense emotional experience, crippling tactics aggravated by physical exhaustion and isolation.” (p.86).

Similarly, lies or even “being economical with the truth” appear designed to recruit people through a process of extracting commitment and then forcing a decision. For example, RC initially offers low cost, peer group counselling. The full extent of the group’s organisation and programme is not immediately made clear. Nevertheless, a commitment to some form of counselling activity is obtained, and sounds on first hearing much more acceptable than joining a crusade to save the world. A person is likely to imagine that they have delayed a decision to make such a total commitment, perhaps indefinitely. However, they soon find their initial levels of activity rising: “come to one more class,” “attend one more workshop,” “read an extra pamphlet this week.” Whether they have consciously decided anything becomes irrelevant: a real commitment has been made to the organisation. They may then find that their attitudes are changing to come in line with escalating levels of commitment, and will eventually reach such an intense pitch that a formal decision (if it needs to be made at all) is only a small final step – a classic demonstration of cognitive dissonance theory (Turner, 1991). The manipulation of this process is, of course, a hallmark of salesmanship in general, whether the products are second hand cars, encyclopedias or global salvation.

Temerlin and Temerlin (1982) list a number of characteristics which they argue are common to psychotherapy cults, and which in terms of the above discussion can be construed as mechanisms for engineering consent. Summarised briefly, the following are the suggested main criteria for the identification of psychotherapy cults:

1. Charismatic leader figure, with authoritarian and narcissistic tendencies;

2. Idealising of leader by followers. Frequently the leader is hailed as a ‘genius’, and is at least considered the supreme exponent of the group ideology;

3. Followers regard their belief system as superior to all others, and a more rational investigation of alternatives or the empirical verification of key concepts is discouraged.

4. Followers frequently join group at time of exaggerated stress in their own lives, when confidence in their own independent judgment is likely to be low.

5. The therapist becomes the central focus of follower’s life. The group concerned absorbs increasing time, energy and commitment.

6. The group becomes cohesive. Illusions emerge of superiority to other groups. In particular, much of its energy is focused on idolatry of leader.

7. The group becomes suspicious of other groups. Links with others are discouraged, ensuring that ideas which do not originate within the group are ‘translated’ for the group’s benefit by leader figure.

It is clear that these processes are particularly applicable to organisations which depend largely on group based activities. There is considerable evidence to suggest that group attitudes are inherently likely to be more extreme than individual attitudes (Moscovici and Personnaz, 1969). Janis and Mann (1977) have established that groups also have a tendency to develop illusions of invulnerability, an exaggerated sense of optimism, and stereotypical images of other groups, while silencing dissent in their own ranks, compelling members to suppress their own feelings of doubt in order to conform, and develop illusions of unanimity (since outward expressions of dissent are curtailed).

Many organisations and groups are aware of these processes, see them as problems which impair objective decision making and take steps to counteract their influence (Moscovici and Doise, 1994). Cult organisations, on the other hand, sustain and exaggerate them, since by definition their existence requires uniformly slavish behaviour on the part of members. The problem is compounded because it seems that even as individuals we have a tendency to exaggerate the correctness of our own decisions, mislabel the behavior of others and imagine that our judgements are more soundly based than they actually are (Sutherland, 1992). This tendency can be manipulated in the context of group membership, to give people an exaggerated sense of the group’s uniqueness and level of insight into the problems which society faces. In contrast, it has been shown (Hirokawa and Pace, 1983) that better quality decisions are reached by thorough examination of options and the setting of rigorous criteria for decisions, alongside systematic examination of the validity of assumptions, opinions, inferences, facts and alternative choices. It is precisely this iconoclastic approach which cultist organisations discourage. Thus, if we follow a group which reproduces the habits outlined by Temerlin and Temerlin (1982), our capacity for independent judgement is seriously impaired, our attitudes will develop along lines prescribed by the leader of the group rather than what logic, observation or personal experience might dictate, we find ourselves deprived of sufficient information to choose between a variety of options and it is possible for the leaders of the group to engage in behaviours which to an outsider can only be described as abusive.

If you want more, the Ross website is a good place to start, with lots to read and plenty of links. Information is power, and there is always more to be learned.

Watchers, keep watching!