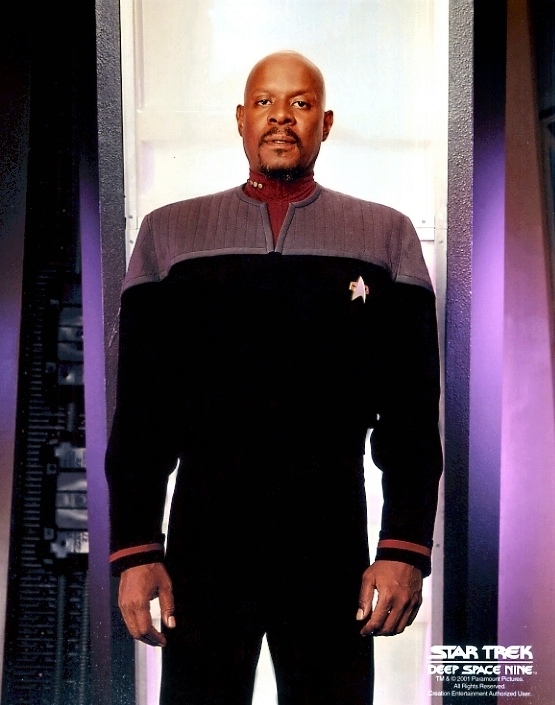

Photo — The amazing Avery Brooks as Captain Sisko

As food for thought, and as a meditation for the New Year, I offer my thoughts on the significance of the past, with some reflections on LRH and Star Trek: DS9 in the mix. Enjoy, and I wish you joy and blessings in the New Year!

••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Liminal. I have a friend who is very fond of that word. “I am in a liminal space, in terms of where my life is headed right now.” I heard him say this many times a few years back, when his life was in flux. What does it mean? “Liminal” means “on a boundary or border”. Another way to say it might be in between, or “border-ish”, to borrow a term from Stephen King. Psychologically, to be in a liminal space, like my friend, generally means to be in transition. Crossing over from one place, stage, or state of being, to another. The liminal space is that place which is both, and neither. The place where the old is dying, and the new is being born, and neither process has reached fruition yet.

Birth. The solstices, New Years Eve. The end of the 13th b’ak’tun in the Mayan calendar. Death. These are collective experiences of the liminal. Birthdays, weddings, graduations, changing jobs, leaving a church, divorce, illness, death. These are personal experiences of the liminal. When we find ourselves in a liminal space, we are called — in ways both big and small, subtle and profound — to lay the old to rest, as we begin to perceive what is newly emerging in our lives and make space for that to grow.

What does it mean, to lay the old to rest? “The past is past”; “water under the bridge”; “baggage”. Clichés which make it clear that in our culture we presume that the past is useless, a burden to be left behind. Carrying “baggage” means we are holding on to past experiences in a way that creates a burden in the present, and a barrier to the future. Putting the past behind you is presumed to equate with opening the way for new — and better — things to come. There is truth in this idea, but a problem arises when we carry it too far. It is important that we do not end up seeking an escape from our past and the impact of our experiences, in the belief that this will somehow make us whole.

My training as a healer includes extensive education in a field known as Somatic Psychology. Body-centered psychotherapy, and Dance/Movement therapy are the modalities I practiced when I was a therapist. This included a great deal of training in trauma issues, and pre- and peri-natal experiences. One of the foundational precepts of my training was that the way we have dealt with the pain, injuries, and overwhelming experiences of the past has a direct bearing on our ability to function and thrive in the present. Conversely, our way of being in the moment — movement, posture, breath, our blind spots, strengths and limitations, and habits of thinking — offers a great deal of information about our past experiences and how we have coped with them. Especially when we are not conscious of the memory, or of it’s true impact on us.

Scientology watchers will see that there are certainly parallels with scientology in my training. Naropa, where I was trained, and it’s associated programs such as Windhorse and Friendship House, have been a good place for some very troubled ex-scis to land, because of this parallel. The past is incredibly important in traveling the “bridge to total freedom”. Auditing is essentially a process of calling up (or mocking up) memories, fleshing them out in detail, and then applying a type of emotional extinction technique to eliminate the ostensible impact of the past in the present. However, Hubbard did not invent any of these concepts. Pre- and peri-natal memory, memory retrieval and extinction, and trauma disorder theory did not come from the “Source”.

In my experience, for ex-scientologists, researching the origin of these concepts and how they evolved can be a valuable part of shedding the cult programming. (It is not the topic here, but I will offer some links at the end for those who are interested.) Hubbard co-opted these ideas and twisted them to his own ends, and part of that was to convince people that past is pathology. Instead of regarding our personal history as a source of information and fodder for growth, he portrayed it as something to manipulate or shed — using his “tech”, for a small fee. This was, of course, an important element in keeping his “church” profitable. Everyone has a past, no one is conscious of the whole thing.

The past can serve as a kind of catch-all, where we can put the blame for everything that is wrong now. LRH sold the seductive idea that we can somehow return to some native state of infinite potential and calm, if only we can “unmark” ourselves by erasing the past — or certain select parts of it. The presumption being that the lingering impact of our past experiences and choices, in this life, can only be what keeps us stuck in our confused and limited state. In scientology, auditing serves to free us from this inherently limiting impact of our past. When we reach the limits of our past in this lifetime, we delve into past lives and their impact. Eventually, we confront that impact as an external, invading parasitic force, known as body thetans. The past is literally a pathogen, and must be sloughed off in the name of “survival”. Of course, this is easy to interpret as a projection of Hubbard’s own unwillingness to take responsibility for his actions and choices, and their lingering impact.

Hubbard seems to have created an entire system designed to negate the reality of his own unpleasant past — by erasing what he could with lies and processing, and diminishing the importance of the rest by inventing a context of billions of years. A context in which the span of one lifetime, and certainly one act within that lifetime, is utterly insignificant. The core identity becomes an abstraction, a “thetan” that has experienced everything and is limited by nothing — an empty assertion describing something that has no meaningful way of manifesting within our human experience, with it’s inevitable messiness, limitations and confusion. There is nothing you (as a thetan) don’t already know, and nothing ever to correct or apologize for, because the “whole track” renders it all unimportant. There is nothing you cannot do or be, no human limitation or obligation you are subject to. This is an incredibly corrosive ideology, which demands that you renounce your humanity — the part of you that can be deeply affected by your experience, and carry that impact forward into the next experience, as well as feel compassion and empathy for the limitations of others. It is a recipe for dissociation, even psychosis, and sociopathic behavior.

It is also a reflection of a cherished conceit in our western culture. Whatever the agenda — planetary clearing, self-actualization, total enlightenment, etc. In America, we are very fond of the idea of “reinventing” ourselves in the name of moving forward. We firmly believe in the promise of “starting over”, of beginning a “new chapter” in our lives. We “wipe the slate clean”, “cut all ties with the past”, or “find closure”, so we can “keep it moving”. We are even willing to embrace disaster or catastrophic loss, by focusing on how it provides us a “new beginning”. We will kill a relationship or partnership that is still viable, but in need of nurturing — “let it burn” — so we can find a new happiness sprouting from the ashes. Or so we say.

Is this really true? Is the secret of happiness and well-being contained in our ability to sever ourselves from what is past, or to manipulate and control its impact? No, experience has taught me that this is a kind of escapism. It is the product of a deeply dysfunctional value system that revolves around denial and abdicating responsibility for the impact of our actions and choices. It is a way of compensating when our functioning creates a result we dont wish to deal with. It is Mark McGuire, sitting in front of a congress investigating performance-enhancing drugs and talking about how he does not want to dwell on the past, as a way to avoid simply saying what he did and when. It is the government, refusing to investigate clear evidence of heinous war profiteering by American defense contractors in Iraq, because it is too painful and divisive to look at and we need to move on. It is L Ron Hubbard, ditching his wife and taking to the high seas on a grandiose mission to save mankind, in order to evade responsibility and avoid scrutiny for his dishonest actions and false promises.

The true value of the past is revealed when we confront it head on, and own it as a part of who we are today. This is how we keep moving forward on whatever path is formed by our life circumstances. Think of it this way: our experiences are the ground on which we walk, and our habitual response or applied training and wisdom are the way we walk that path. The impact of the past exists as a charge or momentum in our movement. Attempting to deny that impact collapses that charge and has the paradoxical effect of keeping us stuck in those past experiences. If we have done something wrong, our feelings of remorse and responsibility are what drive us to make amends. When we have been hurt or suffered a loss, our pain and anger can propel us to seek justice or find some way to make our loss meaningful. When we acknowledge our past and the emotional impact it has had on us, emotion becomes a momentum, propelling us forward.

Which brings me to an episode of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine that explores these ideas in an elegant fashion. The title is “Emissary”, and it is available on DVD, Netflix streaming, iTunes, etc. (season 1, episode 1). In this, the premiere episode of this series, we are introduced to some great characters in a difficult situation, where they must live in the aftermath of a very ugly past. In particular, there is Commander Sisko, the “captain” in this series. He is a Starfleet officer, a war veteran, and a father, who lost his wife years earlier under terrible circumstances, in the midst of battle. He has never dealt with this traumatic loss, and is a very bitter and tortured man because of it. Now, he finds himself stationed on a distant post, in a turbulent area, with a young child; he is unhappy, and he is contemplating a “clean break” with the past.

Before he can do that, however, he has a mission to carry out. In the process, he finds himself dealing with spiritual matters, and strange artifacts that give him a vision of his painful past. Ultimately, Sisko is led to an encounter with entities known as “the Prophets”; aliens who live in a “wormhole”, outside our space-time continuum. In the process of making “first contact” with these aliens, Sisko finds he must explain such basic concepts as time, death, and love. His communication with these aliens is entirely telepathic, and they use people and images from his own memory as a medium and context for the conversation. Thus, Sisko finds himself talking to his late wife, his child, and others from his past as he attempts to explain. Revisiting key moments in his past, the Prophets probe him for understanding of the nature of his existence. Linear time is a very strange concept to them, and Sisko attempts to explain how we leave the past behind and move towards the future. He even attempts to use baseball as a metaphor, as seen in this clip.

Yet, they keep returning to the traumatic moment in time when Sisko lost his wife, and the prophets ask, “if all you say is true, then why do you exist HERE?” Confronted with her body, Sisko asks “why do you keep bringing me here?” The prophets reply, “we do not bring you here, YOU bring US here. You exist here.”. At first, Sisko does not understand. When he finally stops, and really looks at where he is, he breaks down and finally grieves his loss. The Prophets help him realize that the nature of his existence is NOT linear. The past is always with us, and how we relate to it is a part of our existence in any moment. (see the clip here)

I highly recommend this episode, and the entire series. Sisko’s journey is a remarkable one, from the perspective of trauma and healing, and the role of spirituality and destiny in our lives. There are other equally compelling characters, and each one has a past they must confront and learn from. Major Kira Nerys, a former guerilla fighter on an occupied planet, who must learn how to cope with peace and freedom. Jadzia Dax, who has a unique physiology as a “joined” being, a young woman with a very ancient parasite inside her, sharing her consciousness and seven lifetimes of memories. Odo, the “shapeshifter”, who has no idea what he is or where he comes from. Deep Space Nine is all about reconciling the past and coping with an unforseen future. It is dark, and contemplative, and ironic. It is my favorite Star Trek series. I hope you check it out, and allow it to inspire some reflection on the meaning and value of the past, as we move into a New Year.

Peace.

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Some informative links; explore them!

– An article on memory extinction, including a basic definition:

“Memory extinction is a process in which a conditioned response gradually diminishes over time as an animal learns to uncouple a response from a stimulus”

-Memory extinction research at Scientific American

-Pre- and peri-natal psychology article on Wikipedia

-Pre-natal memory research at Scientific American

-Another therapeutic approach using Pre-natal and early memory

–Somatic Psychology article on wikipedia